The Real Frankenstein and Its Author

Did we misread who the true monster author was?

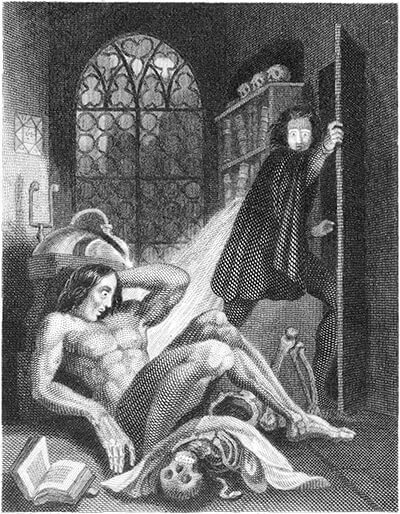

This year is the bicentennial of Frankenstein, the most famous work of English Romanticism; it was published anonymously on Jan. 1, 1818. To commemorate the anniversary of its first publication, events and conferences will be held all over the world, and feature articles have already appeared in The New Yorker, The Guardian, and The New York Review of Books.

Even so, most readers of Frankenstein (its complete title Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus) have not understood or appreciated it. Most of them have read the bowdlerized 1831 edition, the only one available for more than a century, rather than the original 1818 edition, and they have come to it with the wrong expectations. Frankenstein is not just a horror story about a monster; it is a moral allegory, a radical and powerful novel of ideas. It is great literature, which contains some of the finest prose in the English language.

My 2007 book, The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein, has three theses:

- Frankenstein is a great work, which has consistently been underrated and misinterpreted.

- The real author is Percy Bysshe Shelley.

- Romantic male friendship is a central theme.

I have received a lot of flak for the second thesis, and yet it is the one with which virtually all of my readers agree. In 2007 I gave a talk at a Regional Gathering in Boston, and I asked at the end whether anyone still thought that Mary Shelley (the former Mary Godwin) was the author. Everyone laughed and said, no, I had convinced them that she was not.

How do we determine authorship? Not from handwriting, although Mary Shelley advocates intransigently try to do so. The reality is that she routinely acted as copyist for Shelley and for other authors. There exist manuscripts where all of the words are in her handwriting, but all were indisputably composed by someone else. Obviously, therefore, handwriting is irrelevant to whether she wrote all, most, a little, or none of Frankenstein.

Nor should we attribute authorship on the basis of extratextual evidence because some of it is fake. Shelley, for reasons unknown, didn’t want to claim authorship of Frankenstein, and he tentatively tried to fob off authorship on his second wife, Mary. He died in a boating accident in 1822. The hoax entered its second phase in 1823, when Mary’s father, William Godwin, prepared a second edition to coincide with a London play, Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein. Acting entirely on his own, Godwin made 123 substantive changes to the work; he prominently named the author as Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley.

In 1831 Godwin and daughter prepared a revised (or bowdlerized) edition, which eliminated or greatly reduced political radicalism, religious skepticism, homoeroticism, and a hint of incest. A keen interest in science was replaced by a soppy religiosity. Stylistically, the 1831 changes were always for the worse.

The 1831 edition is notable for its introduction, which created a famous myth: In 1816, Mary Godwin, a teenage girl, takes part in a ghost story contest in Geneva, with Lord Byron; Byron’s personal physician, Dr. John Polidori; and her companion, Percy Bysshe Shelley. For several days the gentlemen wait impatiently for her to come up with a story. Finally, she has a nightmare, which inspires her to write a story, “which would frighten my reader as I myself had been frightened that night!”

None of it is true. Byron was not fond of Mary Godwin; he would invite Shelley to dinner, pointedly not inviting her. Polidori’s diary indicates only one occasion when she and her stepsister, Claire Clairmont, stayed the night in Byron’s palazzo. The preface to Frankenstein, written by Shelley and published in all editions, clearly indicates that the participants in the ghost story contest could only have been Byron, Polidori, and himself — three brilliant young men who were already accomplished writers.

The 1831 introduction bears no resemblance to anything Mary Shelley ever wrote or to the Frankenstein prose, but it closely resembles the writing of William Godwin, both in style and ideas. Godwin wrote it from his daughter’s perspective, acting as ventriloquist, with her as the dummy. He was a good novelist — Things as They Are; or The Adventures of Caleb Williams is a page turner — and his Frankenstein introduction is an enduring work of fiction.

Frankenstein is a moral allegory about the evil effects of intolerance, addressed to the victims of intolerance and to society at large.

Textual evidence is what matters: the prose of Frankenstein, the prose of Shelley, and that of his wife. Determination of authorship could hardly be more decisive. Any good reader will recognize Shelley’s hand through comparison with his early novels, Zastrozzi: A Romance and St. Irvyne or The Rosicrucian: A Romance, and with his other works. Every page of Frankenstein bears Shelley’s signature — his ideas, erudition, and mastery of English prose.

There are great women writers, but Mary Shelley was not even a good one. The prose she really wrote entirely on her own is flaccid, sentimental, verbose, and sometimes ungrammatical. Nowhere is there the slightest trace of the Frankenstein genius.

Frankenstein is a literary masterpiece. At times it has the deceptive simplicity of a fairy tale; at times, as in the animation of the monster, the intensity of Edgar Allan Poe; and at times, as in the famous dream sequence in chapter 4, it anticipates surrealism. The best passages are prose poetry of the highest order.

Frankenstein is a moral allegory about the evil effects of intolerance, addressed to the victims of intolerance and to society at large. This was the opinion of Shelley himself, who in a posthumously published review of his own novel (yes, authors did and still do review their own books) wrote that the moral is, “Treat a person ill, and he will become wicked.” He wrote: “Too often in society, those who are best qualified to be its benefactors and its ornaments, are branded by some accident with scorn, and changed, by neglect and solitude of heart, into a scourge and a curse.”

Most readers identify with the Being (aka Creature, daemon, monster, etc.) and sympathize with his undeserved sufferings. In my book I say that the Being stands for every victim of intolerance: “schoolboys, tormented and bullied for being too sensitive; lonely old women, tortured and executed as witches; gay men, hanged for loving each other; freethinkers and heretics, burned at the stake for their ideas — all those who have suffered because their appearance, culture, behavior, or beliefs were different from those of the majority.”

We in Mensa can identify with the Being, who is not only of superhuman size and strength but also (unlike the movie monsters) of superhuman intelligence. A newborn creature, he masters French, German, and English on his own in a few months. His speeches are superbly eloquent.

We with abnormally high intelligence differ in our social skills and experiences. Some of us successfully use our intelligence in interacting with the less intelligent and get along fine with them; some of us find or create environments with others of high intelligence.

Others are not so lucky. Aaron Clary in Curse of the High IQ (2016) describes how “society is becoming increasingly hostile to intelligent people.” Average people can fear and resent us. We can be ostracized by peers, teachers, employers, and even parents. We are subjected to hostile propaganda, as with the movie Village of the Damned (1960, remake 1995), in which super-intelligent children are demonized as monsters from outer space.

The Frankenstein monster desires “love and fellowship” and futilely yearns for another being “with whom I can live in the interchange of those sympathies necessary for my being.” We too need the companionship of our own kind. Although we can find companionship with average people, that often involves slowing down our minds and dumbing down our vocabularies. We need Mensa and each other.

I recommend reading or re-reading Frankenstein in the 1818 version, alert to its ideas and the beauty of its prose.

John is a retired market research analyst, now a fulltime writer and publisher, who lives in Dorchester, Mass. He graduated from Harvard College with a bachelor’s in 1963. John has a dozen books to his credit. The most recent are The Shelley-Byron Men: Lost Angels of a Ruined Paradise and Don Leon & Leon to Annabella, the first scholarly edition of a 19th century epic poem.

John is a retired market research analyst, now a fulltime writer and publisher, who lives in Dorchester, Mass. He graduated from Harvard College with a bachelor’s in 1963. John has a dozen books to his credit. The most recent are The Shelley-Byron Men: Lost Angels of a Ruined Paradise and Don Leon & Leon to Annabella, the first scholarly edition of a 19th century epic poem.

Boston Mensa | Joined 1984