The Best Toy Ever

They don't make burn hazards like they used to

I was a science nerd at a young age, spending hours poring over National Geographic when the space shuttle was still a far-future concept and Ham the Chimp was a reluctant astronaut.

I had a meager chemistry set during grammar school until the day I spotted the mother of all Gilbert chemistry sets sitting by the curb not far from my home on garbage day. I guess someone had gotten tired of science. That was the year I was given a junior lab bench for Christmas. After I completed modifications, it had a sink that drained into a bucket and running water from a gravity-fed reservoir above. I spent most of my lawn-mowing money on laboratory glassware and replacement chemicals from the local hobby shop. Fire was a major attraction. Many experiments involved a small alcohol burner.

Some of the toys I played with were dangerous, and that’s part of what made them fun. Mattel didn’t intend for their products to be harmful, but apparently safety wasn’t top of mind in the 1960s. And that’s intriguing because Underwriters Laboratories’ headquarters was just a few miles from my house in Illinois. Founded in 1894, the safety organization had plenty of time to ramp up testing of toys by the time the following childhood marvels hit the market, but I’m glad they didn’t.

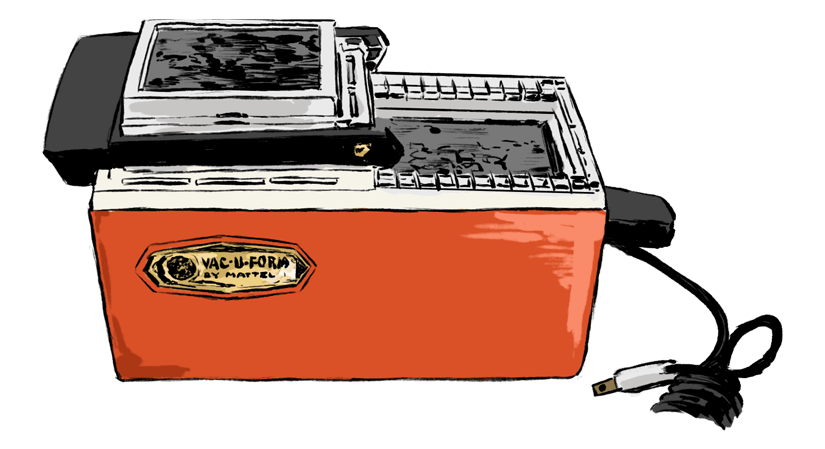

The first was called Vac-U-Form. Sort of a 3D printer of its day, this was the source of great fun for imaginative 10-year-olds in the early ’60s. The name was aptly descriptive. Square sheets of colorful plastic were clamped into a holder and heated over a hot plate to moldable softness then flipped onto the other side of the device. Forming a vacuum, the user then frantically pumped the air out of an underlying chamber upon which the desired object rested, about to be encased in softened plastic that quickly hardened when heat was removed. Presto! You had a mold of your target object.

In my case, that was often the body of an Aurora HO Scale Slot Car. I carefully removed the excess plastic with an X-Acto knife and painted the molded car body for substitution on a bodiless chassis. Sales of consumables for this toy must have been significant. Me and my friends went through stacks of plastic squares in an afternoon.

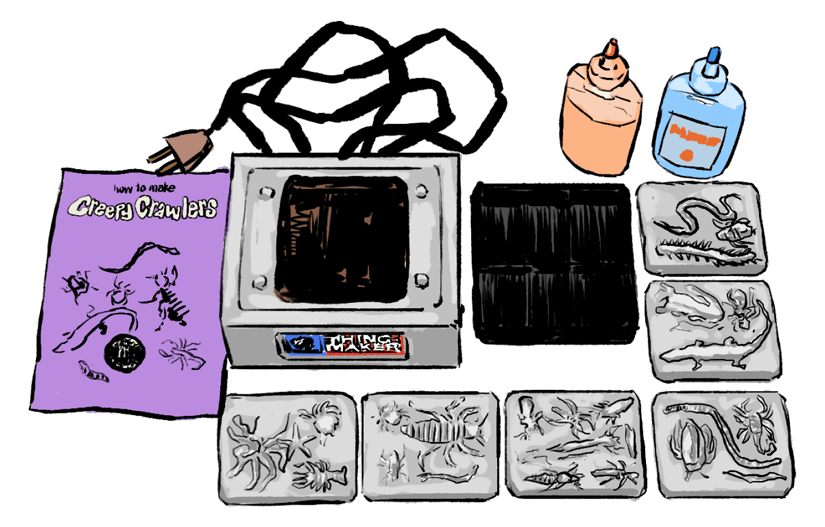

In 1964, Mattel’s Creepy Crawlers, or the Thingmaker, made its debut. Flesh-searing hotplates were all the rage, inspiring another 390-degree kid-burner. At least s’mores over a backyard campfire come equipped with sufficiently long handles. Not this device, though.

The toy came with a series of die-cast metal trays, each with an assortment of bug impressions into which “Plasti-Goop” liquid was poured. The colors of Goop multiplied as the popularity of the toy increased. Soon there were fluorescent variants of the original, somewhat dull rainbow, including a glow-in-the-dark greenish radium color.

You simply filled the molds with Goop and then heated until a noticeable color change indicated that the plastic had cured. After a bit of cooling, you pried the insect from the mold with a pointed metal stick. Bottles of Goop didn’t last long at the rate we created our creatures. Up until this point, fake bugs were acquired one at a time from clear plastic eggs in a grocery store gumball machine at the cost of up to 25 cents each. With the Thingmaker, we made hundreds of them! This toy line became a franchise unto itself, spinning off dozens of themed sets all the way into the early 1970s.

When I had kids of my own, I was thrilled to see that these toys still existed. Sort of. By the 1990s, safety-conscious manufacturers substituted hot plates for light bulbs, encasing the previously open and accessible scalding surfaces deep within the machine. They took forever to work due to lower heat and were just not that fun. My kids never enjoyed them much.

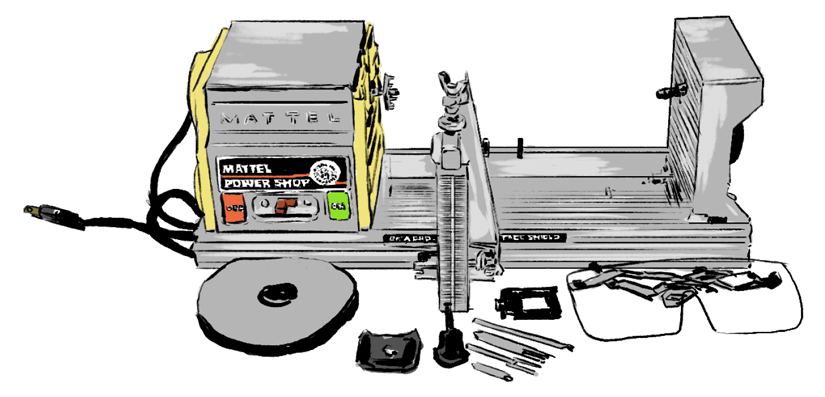

The final member of our Mattel triad was the Power Shop. This was a truly useful little woodworking tool that morphed into one of four configurations: jigsaw, lathe, disc sander, or drill press. It came with an assortment of balsa wood pieces and project ideas but could handle much more.

I used all four tools to make a little cannon. I carefully turned the barrel on the lathe, creating a sculpted shape from a square block of wood. The resulting pile of wood shavings raised the sweet smell of pine sawdust that I later came to enjoy in high school woodshop. The jigsaw removed excess material to form the spokes of the wheels, and the drill press created the holes in the wheels for the axles. Everything was sanded to a smooth finish. The project occupied me for many hours.

Within my chemistry set was the one special toy that didn’t end up going wherever toys end up when you age. It was so intriguing I kept it. When I acquired the set from the curb, it included a small, black device that looked like the eyepiece for a microscope or maybe a jeweler’s loupe. I discovered it was actually a spinthariscope, a toy version of a tool that allows a viewer to observe the nuclear disintegration of ionizing alpha radiation on a surface coated with radium or another phosphor.

The Gilbert Company created the U-238 Atomic Energy Lab, parts of which had been combined with the chemistry set I found. The appeal of these activity toys was the way they encouraged ingenuity. While Creepy Crawlers limited the resulting output, Vac-U-Form and Power Shop allowed experimentation and the ability to go off-script, much like my earlier chemistry set.

Flesh-searing hotplates were all the rage, inspiring another 390-degree kid-burner.

Now, after the lights go out and my eyes have adjusted to the dark, the greenish remnants of radioactive decay sparking and streaking across the dark field within the eyepiece continue to amaze me. There’s no ON switch. The particles have been randomly striking the spinthariscope and everything around me, everywhere and always, since the last time I looked. It is a humbling experience, witnessing the evidence of cosmic elements that are otherwise described only in books or on science television.

To say this makes me feel one with the universe would be hyperbole, but it sort of forges a connection. The persistence and ubiquitous nature of these particles, some of which effortlessly pass through the human body at perhaps 4 percent of the speed of light, speak to the greater mysteries of the universe and the brilliant minds that have postulated and then proved their existence.

I’m grateful there were no computers or video games when I was young. The educational, interactive nature of these and other toys led me to a career in medical laboratory science, research and development, and, eventually, science writing.

Best toy? Maybe you remember another.