In the Company of Heroes

WWII film honors Greatest Generation's service and sacrifice

In the early hours of May 29, 1945, Lt. Royal A. Stratton and his crew from the 4th Emergency Rescue Squadron boarded their amphibious aircraft, a PBY Catalina christened Pistofe, and took off from South Field airstrip on the diminutive island of Iwo Jima. Eight weeks earlier, after a protracted 36-day assault, the volcanic island had been taken by the U.S. in one of the bloodiest battles in Marine Corps history.

The island had been designated a strategically imperative military objective. There, Navy Seabees rebuilt its airstrips for Air Force pilots to use as a place of rescue for battle-damaged B-29s returning from missions over the home islands of Japan.

On that Tuesday morning, Stratton and his crew, who had been stationed on the island, were charged with locating the downed airmen of the B-29 Dragon Lady. The Superfortress had sustained catastrophic flight control and electrical system damage from Japanese anti-aircraft flak. Forced to ditch their plane, the crew was adrift and unprotected in the open ocean of enemy waters between Tokyo and Iwo Jima.

Stratton would locate and rescue those nine men, but he would never return from that mission.

* * *

When my film production partner, Christopher Johnson, first shared with me the story of his great-uncle Royal and the rescue mission that claimed his life, I couldn’t stop thinking about that 22-year-old pilot who put on his Army Air Corps uniform one day, kissed his wife and his 4-day-old daughter goodbye, and set off for the South Pacific, unaware that he would never see them again.

What a profound sense of duty young soldiers must have to leave behind all they know and love to serve a cause greater than themselves. When I learned that the men of the 4th Emergency Rescue Squadron were flying into combat zones without armament — their aircraft machine guns having been exchanged for space to accommodate the rescued — for the sole purpose of saving lives, I was thunderstruck. With more than 6,000 hours of flying time, this intrepid squadron conducted 862 rescue missions, saving the lives of 576 men. The moment I heard those service statistics, I was all in. I needed to contribute to preserving their legacy and ensuring their service, dedication, and sacrifice would not be forgotten.

So, I signed on to produce the film Journey to Royal: A WWII Rescue Mission.

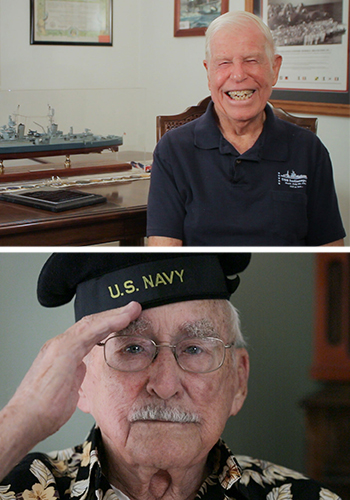

Using dynamic cinematography and gripping live action, combined with firsthand accounts and historical images, we would showcase the valor of this squadron and its members who faced overwhelming odds to bring their brothers home. The result would be a film featuring World War II veterans who served in a capacity antipodal to a common perception of wartime service. It would be a film spotlighting a never-before-told aspect of the war: the mission of the Army Air Corps rescue squadron.

* * *

Motion pictures take a long time to develop, and once production begins it’s typically between one to three years until a film is completed and distributed to an audience. With Journey to Royal, the decade-long production period required endurance on a sustained level that, in hindsight, is daunting to consider. Because of the film’s hybrid narrative/documentary aspect, we needed to shift gears fluidly between scripted sequences that unfolded traditionally and documentary sequences that were more exploratory and open-ended. The scripted sequences, which translate to 30 minutes of screen time, were derived from 30 pages of shooting script. The documentary segments, which comprise the remaining 60 minutes of the film, were culled from more than 600 pages of transcribed interviews.

Staring at that copious harvest of dense historical material and knowing only a fraction of it would serve the particular story we were telling was intimidating. We could easily make 10 equally compelling films with the content we’d amassed. Each of the stories in that collection reflects a unique heroism and deserves to be commemorated, which is why we’re actively developing a format to present that additional material. But that’s for another day.

From the start, fidelity to historical accuracy was of paramount importance. That translated into us meticulously handcrafting functional set pieces and props, such as Mae West life vests, E-2 and Type D Mark IV life rafts, and scale miniatures of a PBY Catalina and a B-29. We viewed each of the 1,500 audition tapes submitted by actors for the 18 roles in our feature sequences with the specific intention of finding and casting people whose talents and appearance would best convey a 1940s authenticity. We embraced the opportunity to film inside antique warbirds. With their vintage smells and timeworn textures, we could feel the spirits of those soldiers who had once occupied the legendary aircraft. It became an immersive theatrical experience, which markedly aided the actors in finding their way into character and grounded the filmmaking process in a haunting realism.

One of the most challenging but gratifying tasks of producing this picture was painstakingly searching through names on declassified military accident reports and becoming amateur detectives, putting together disparate clues to track down surviving veterans and their family members. It took years to locate and contact the people whose interviews constitute the documentary portion of Journey to Royal.

* * *

Humility seems to be a vanishing virtue. In this 21st century, there exists a pervasive need to have one’s self-worth validated, regardless of merit, by capturing the fickle and fleeting attention of the masses. Sitting serenely engaged with people of the Greatest Generation and their disinclination to view any of their achievements as distinctively laudable was a powerful reminder of the steadfast mettle that exemplified a generation that persevered with hard-won resilience and quiet fortitude. That humility was present in every single home, with every single person we interviewed for the film, including actors from the golden age of Hollywood whose careers were dependent upon public recognition. Even in those places, a genuine deference to the gravity of the war experience was omnipresent.

An unexpected and affirming side effect of the interview process was the overwhelming response from family members who were present during the filming of our veterans’ interviews. The recurring refrain was sincere gratitude for the opportunity to learn of their family members’ previously undisclosed wartime service history.

The majority of these veterans had never shared their experiences in the decades following the war. When we initially contacted them and presented what we were doing as a preservation of history, these veterans stepped up as if it were an extension of their military service to impart that information, setting aside any feelings of discomfort the recollections might stir in them. Seventy years later, their inherent sense of duty remained resolute.

In those poignant moments, as the veterans discharged the vivid memories of their lives in service, Chris and I became the custodians of their history. That bestowment has been an honor, a privilege, and a responsibility we’ve taken very seriously and have done our best to fulfill. Not just for the members of the 4th Emergency Rescue Squadron and the men whose lives they saved but for all those who didn’t make it home from war — those brave individuals who forever set aside everything they could have been in the name of freedom.

* * *

We set out to tell a particular story. What we couldn’t have imagined at the start was how much richer and more expansive that story would become as we learned of the myriad ways the 4th Emergency Rescue Squadron intersected with the most consequential events leading to the end of the war.

Even those with a cursory knowledge of World War II recognize the iconic photo depicting six U.S. Marines raising the flag on Iwo Jima. Some may remember the haunting monologue delivered by Robert Shaw in Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, as he recounted the USS Indianapolis disaster. To sit across from the veterans who made that history has been a rarefied and unforgettable experience. From the attack on Pearl Harbor to the battle of Iwo Jima, from the delivery of the first atomic bomb to the delivery of the surrender documents, the members of the 4th Emergency Rescue Squadron were there bearing witness. Against a backdrop stained with the horrors of war, they were there saving lives.

This film is our contribution to preserving that ever-endangered alliance between the present and the past. This is our offering to members of the Greatest Generation. They are fast leaving us now, and only a gossamer thread remains to tie us to that important history. They’ve made us who we are and shown us what our better angels can do, and it’s our fervent hope that we never forget.

* * *

Journey to Royal: A WWII Rescue Mission is available on streaming and cable platforms and from all major retailers. For a full list of where to watch, visit journeytoroyal.com.