Do Nonhuman Animals Have Rights?

A practical framework for a reasoned philosophical debate

The nonprofit “Our Planet. Theirs Too.” established National Animal Rights Day (NARD) in 2011. June 7 marks the 10th annual recognition of NARD, which the organization says is “observed in multiple countries around the world on the first Sunday in June for the purpose of giving a voice to all animals and raising awareness for their rights.”

As a philosopher, I find the observance of this day and the language in the NARD statement intriguing. The effort to recognize and educate people about nonhuman animal rights presupposes that nonhuman animals have rights. But this presupposition is not obvious, despite the impression that the nonprofit organization gives to the contrary. In the discipline of philosophy, there is a legitimate debate over whether there are such things as nonhuman animal rights. Indeed, philosophers have debated whether human beings have objective moral rights.

The 19th-century British philosopher Jeremy Bentham famously claimed that the concept of human rights is “nonsense upon stilts.” Many contemporary thinkers accept ontological naturalism, which is the view that reality is exhausted by the physical, i.e., everything that exists is physical or reducible to physicality. It is difficult for this worldview to make sense of objective moral rights (human, animal, or otherwise) because such rights are not physical objects. I am not an ontological naturalist, and I hold that human beings have objective moral rights. Nevertheless, I raise the points about Bentham and naturalism to show that philosophers disagree on the topic of human rights; a fortiori, they disagree on animal rights.

In this article, I will articulate one argument to support the position that nonhuman animals (hereafter, animals) have rights and one argument to oppose this position. I will close by addressing some of the practical implications of this topic. My goal is not to defend a position but rather to express plausible arguments on both sides so the reader might see that the topic is not easy and the answer to the question posed in the title of this article is not obvious.

Important Terms

As the American philosopher Roderick Chisholm wrote, readers of a philosophical essay have the right to know how the writer is using important terms. Hence, I will start by providing a short discussion of some key terms upon which the debate hinges.

First, the claim that animals have rights is ambiguous. What kind of rights? Moral rights or legal rights? Here are working definitions for each term. A moral right is a privilege to perform an activity or to access a benefit; the privilege is held by a person in virtue of existing as a person (i.e., a rational moral agent). A legal right is also a privilege to perform an activity or to access a benefit; but the privilege is possessed in virtue of its being granted by state authority. Legal rights are given by and dependent on the government. Moral rights are possessed in virtue of being a moral agent and are therefore independent of government. Arguably, the debate about animal rights is not a matter of legal rights. Such a debate has little philosophical interest. All that would be required to settle the debate would be the passing of a relevant law (or the citing of a germane law that already exists). But if such a law were passed, one could still ask if animals have any real moral rights, wherein lies the debate.

The debate is not about subjective preferences, emotions, or desires regarding the idea of animal rights. In other words, the issue is this: Is it a mind-independent fact that animals have moral rights?

Next, let us distinguish between objective and subjective. The former refers to entities that exist independent of human thought, belief, desire, preference, or choice. For example, the Earth is objectively real. Its existence is independent of the human mind. It would exist even if no humans were around to think or form beliefs about it. In fact, the cosmological, geological, and anthropological evidence indicates that the Earth existed long before the genesis of humans. The latter term means “dependent on human thought, belief, desire, preference, or choice.” Something is subjective if it depends on and is relative to the mind of the human subject. For example, I prefer coffee over tea. I like both; but if I must choose, coffee wins the day. This preference of mine is real. However, it is subjective. Its existence depends on my mind. My preference exists in my mind, not in the object (i.e., the coffee). If I were not to exist, there would be no such thing as my preference for coffee.

This is an important distinction because the debate concerns the objective existence of moral rights for animals. The debate is not about subjective preferences, emotions, or desires regarding the idea of animal rights. In other words, the issue is this: Is it a mind-independent fact that animals have moral rights?

Some support the claim that animals have objective moral rights, while others do not. Let us consider the opposing positions via an argument trying to show that animals have objective moral rights and another attempting to demonstrate that animals do not have them. Each argument is reasonable and is commonly raised in the debate.

An Argument for Animal Rights

Those who support the position that animals possess objective moral rights might argue that every creature that can feel the sensation of pain has objective moral rights by virtue of having the capacity to experience pain. According to this argument, because all animals can be in pain states, it follows that all animals have objective moral rights. The argument can be articulated formally as follows: (1) If a being can feel pain, then it has objective moral rights. (2) All animals are beings that can feel pain. (3) Therefore, all animals have objective moral rights.

On this argument, the capacity to experience pain is taken as a sufficient condition for the possession of moral rights. To defend this argument, one would need to defend the assumption that the mere capacity to experience pain is sufficient for the possession of objective moral rights.

Now, this argument is deductively valid, which means that if the premises — (1) and (2) — are true, then the conclusion (3) must be true as well. So, to evaluate the argument, one must determine whether (1) and (2) are true (or at least more plausible than their negations).

An Argument Against Animal Rights

Those who deny that animals have objective moral rights might object to (1) — that if a being can feel pain, then it has objective moral rights. Why accept this conditional proposition? Instead, one might argue that only moral agents have objective moral rights. Animals are not moral agents. To believe otherwise is to commit the fallacy of anthropomorphism, aka the Disney fallacy. This fallacy (or common mistake in reasoning) occurs when one ascribes human or personal properties to something that is not human or personal, such as an animal or a tree.

This argument that animals lack objective moral rights can be expressed formally as follows: (4) For any creature, if the creature has objective moral rights, then it is a moral agent. (5) Thus, if a creature is not a moral agent, then it has no objective moral rights. (6) Animals are not moral agents. (7) Thus, animals do not have objective moral rights. On this argument, the absence of moral agency is sufficient for the nonpossession of objective moral rights. To defend this argument, one would need to provide reasons for holding that lack of moral agency is sufficient for lack of moral rights.

This argument is also deductively valid. Hence, if the premises — (4) and (6) — are true, the conclusion (7) cannot be false. As with the previous argument, proper evaluation requires an examination of (4) and (6). Are these statements true (or at least more plausible than their negations)?

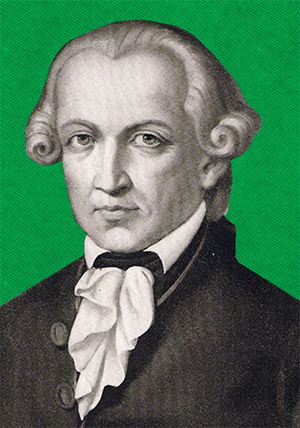

If this argument is sound, it does not entail that human beings are justified in mistreating animals. It only means that animals are not moral agents and therefore (precisely speaking) lack objective moral rights. That is, one can treat animals with care yet deny that they possess moral rights. For example, Immanuel Kant opposed cruelty to animals. He believed that treating animals with respect and compassion helps us to treat persons with respect and compassion: “for he who is cruel to animals becomes hard also in his dealings with men.” As such, Kant argued, we should avoid cruelty to animals. He did not, however, hold that animals have moral rights. He believed that only persons have such rights. Animals cannot follow moral principles such as the categorical imperative or the golden rule. Only persons can understand and attempt to practice such normative principles.

One might object to the argument against animal rights by claiming that it rests on a fallacious definition of “moral right,” i.e., the argument is weakened by the presence of the definist fallacy. This fallacy occurs when one defines a term in an ad hoc manner for the sake of defending one’s position. The advocate of the argument against animal rights might respond that the definition of “moral right” is not ad hoc. Instead, it accurately reflects what we mean when we speak carefully about moral rights.

Practical Considerations

Why is this topic important, practically speaking? For one thing, consider food. What is more practical than food? We eat regularly, and we must do so.

Those who believe that animals have objective moral rights might be inclined to vegetarian or vegan diets. A vegetarian might hold that animals have an objective moral right to life and hence that humans ought not violate that right by killing and eating animal flesh. A vegan might assert that animals should not be used as a means to produce food, including dairy products. On the other hand, those who deny that animals have objective moral rights might conclude that it is morally permissible to eat meat, provided that the animals are not treated cruelly before slaughter.

Moreover, consider the use of animals for scientific testing. If animals have objective moral rights, then using them as a means for scientific development might be problematic. For example, is it morally permissible to use animals for testing to develop drugs or vaccines for COVID-19? However, if animals lack objective moral rights, there seems to be no problem with using them for the sake of developing medicines or other technologies to save or improve human life — so long as the animals are treated humanely. Similar points can be made about using animals for clothing, entertainment, transportation, and sport.

* * *

June 7 is a day to reflect about the topic of animal rights. For the philosophically inclined thinker, June 7 is a reminder to examine claims that might otherwise be accepted in an unexamined fashion. Why is this topic important, practically speaking? Here’s how Socrates might answer the question: because the unexamined life is not worth living for human beings.