Common Threads: An Inspection of the Morgellons Community

Delusional parasitosis or not, Morgies deserve empathy

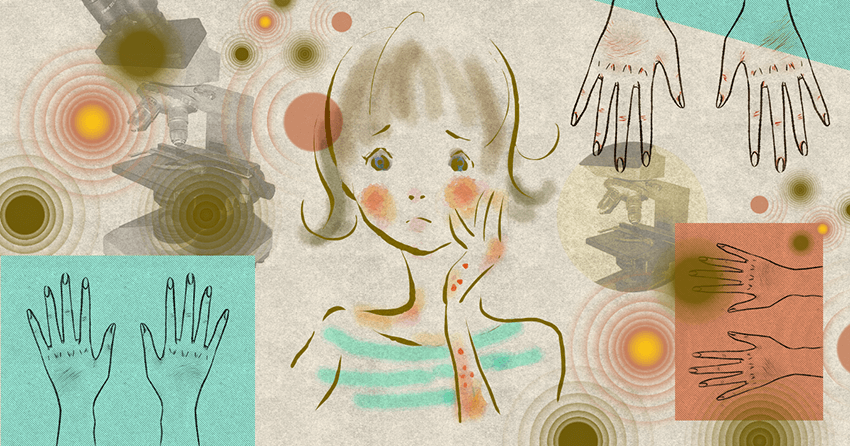

It begins as an itch. Somewhere innocuous, the ankle or arm, feels prickly, and the urge to scratch arises, then multiplies. She begins digging for an unseen object, the subcutaneous invader.

Upon inspection, she might find and extract what appear to be multicolored threads or larva. In a panic, she takes her discovery, carefully concealed in a Tupperware container, to the emergency room. The doctor does not even look at the mysterious object. He diagnoses the patient with “delusional parasitosis.” Dismayed, she takes to the internet, searching for a cure. There she is finally validated: Morgellons disease, an underground illness causing symptoms that sufferers insist have physiological origins but that the medical community is inclined to perceive as delusionary.

Morgellons is notable for its associated complaints of bugs or threads emerging from beneath the skin (known as formication), hence the diagnoses of delusional parasitosis. Additional physical symptoms vary widely among patients and include bodily fatigue, joint pain, a stinging sensation in appendages, and itching, reports 2018 Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology article “History of Morgellons Disease: From Delusion to Definition.” The psychological elements of the disease and the online community of people who have it create an understandable wariness from health care professionals.

More than 75 percent of Morgellons sufferers are self-diagnosed, according to the November-December 2018 Clinics in Dermatology article “Delusional Infestation Versus Morgellons Disease.” Not long after Morgellons was identified and named in 2002, sufferers of the disease coalesced into a community of support for one another, particularly online, united by societal shunning and common symptoms. Rather than to biological causes, many doctors attribute the disease’s surge in popularity to the community around it and the affirmative power of finally receiving some diagnosis.

The patients, generally white, middle-aged women, are often dismissed by doctors and referred for psychological treatment. Hallucinations and delusions are prominent symptoms of the disease, which invite a distracting parallel with other mental disorders.

However, in recent years, instead of dismissing Morgellons as a purely delusional disorder, researchers have also been searching for biological reasons, including bacterial infections that might explain the resulting psychological effects. Although academia attempts to treat Morgellons as a serious disease, its dubious origins still present a challenge. What matters, nevertheless, is the humanity of the people suffering from Morgellons — the pain, whether real or imagined, that they experience daily.

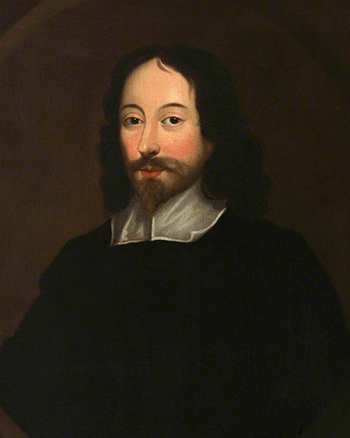

Morgellons burst into the public eye in 2002, with Mary Leitao’s purported discovery of colorful threadlike filaments protruding from her toddler son’s upper lip. Although doctors doubted her, Leitao persisted in her research, eventually finding a 1674 description by Sir Thomas Browne of a childhood malady. He had named the illness Morgellons, the term later adopted by Leitao to describe her quandary. In 2002, Leitao founded the Morgellons Research Foundation to bring awareness to the disorder. At this point, the modern iteration of Morgellons disease took root. It grew exponentially, reaching more than 14,000 self-reported cases by 2009.

For its first 10 years, from 2002 to 2012, Morgellons ebbed and flowed in popularity, primarily existing in the recesses of internet chatrooms but also proliferating through word of mouth. Following an inconclusive CDC investigation in 2012, in which Morgellons was deemed more akin to a delusional infestation than a medical condition, Morgellons once again disappeared into obscurity. Through journalistic profiles, annual conventions, and documentaries targeting both the general public and the Morgellons community, Morgellons has reemerged as a disease worth studying. These pieces make an effort to avoid condemning or publicly shaming the community. Rather, they function to spread awareness and encourage research. They tend to acknowledge that, no matter if the disease is biological or psychological, it severely hinders the lives of those afflicted by it. For that reason, an effective treatment needs to be found.

The Devil’s Bait, an essay detailing journalist Leslie Jamison’s 2013 foray into a large annual Morgellons convention, was one of the first in-depth, impartial accounts of the elusive community.

Morgellons patients, colloquially known as Morgies, gather annually in Austin, Texas, to meet in person, exchange stories of disbelieving doctors, and discuss their collective uncertain future. As Jamison emphasizes, most people suffering from Morgellons are female, white, and middle-class. This combination tends to get cases dismissed merely as “female problems.” Dawn, one of the Morgellons patients in attendance at the conference, described her frustration with the gender bias in diagnostics, prompting Jamison to note: “For a long time, women’s heart attacks were misdiagnosed or even ignored because doctors assumed that these patients were simply anxious or overly emotional. […] Dawn’s disease has been consistently, quietly embedded in a tradition that goes back to 19th-century hysteria.”

The assumption of hysteria is latent in the delusional parasitosis diagnosis, and, eventually, Morgellons has grown to embody centuries of female oppression and assumed hyper-emotionality. To be a woman is to fight for recognition, the challenge most Morgellons patients feel they must overcome before they are taken seriously.

As Morgies push for recognition, they also face daily the physical impacts of the illness: disfigurement and scarring. Body scarring becomes commonplace as patients spend years digging, reopening sores, and peeling back scabs in the hopes of finally finding some respite. The pockmarks can be unsightly and embarrassing, causing shame for the patients. The societal shunning lends itself to their collectivist mindset. Morgellons sufferers find the possibility of refuge in those who are like them, who understand the compulsion. At conventions, Morgies share photographs and videos of their findings and together peer into microscopes, trying to discern what emerged from their skin. They no longer feel shame at their picking but instead feel like they can finally breathe.

Morgellons’ signs and symptoms — bug-like creatures under the skin, compulsive picking, obsessive thoughts — are often associated with drugs, bringing to mind addicts digging into their bodies in the hunt for a subversive terrorist. Normal, healthy humans do not usually self-inflict pain and willingly mutilate their bodies. However, many of these patients are otherwise normal people. They are nurses, electricians, and housewives. They wonder how they contracted the disease and whether they are dangerously close to encroaching upon the land of the insane.

One patient that Jamison interviewed, an older man named Paul, believed he contracted Morgellons on a fishing trip. As the years progressed, not only did his sister contract it as well, but he became desperate to find a cure. At the time of the article, Paul was pouring root beer in his ear to self-soothe. “They experiment with different treatments and compare notes: freezing, insecticides, dewormers for cattle, horses, dogs,” Jamison wrote. These are the cures Morgies are pinning their hopes on because they feel that medicine ignores their plight. The professionals often refuse to help, so sufferers take matters into their own hands.

Morgellons on its own is probably not solely a psychological illness. Analysis of extracted fibers has found that some are composed of biological materials (e.g., collagen), implying that Morgellons may be a form of spirochetal infection, akin to Lyme disease.

Facing repeated disbelief, not to mention the societal shame, is enough to exacerbate any preexisting psychological issues. Sufferers spend so much time trying to prove they are not crazy that eventually they become crazy, burdened with the post-traumatic stress of repeated rejection. People will seemingly pretend to be caring doctors or medical professionals only to swindle money out of the patients, peddling fake cures that are ineffective and sometimes even deadly. A Facebook post from 2012, available on the first page of a Google search for “Morgellons cures,” encourages patients to bathe in a potent cocktail of bleach and alfalfa. The post includes responses from people begging for more than a cursory glance from a medical professional. The most common refrain among patients, repeated throughout Jamison’s article and echoed in the internet’s obscure cures, seems to be a cry for others to listen.

Whether the symptoms are physical, mental, or both, Morgellons disease needs to be given consideration.

The pain sufferers feel is real to them, and the disease’s ambiguous origins do not merit an instant dismissal by the medical community. Until a treatment can be found, these patients need to be seen as people. If doctors become informed about Morgellons disease, rather than just labeling their patients with delusionary disorders and making referrals for psychiatric treatment, they will be able to create more ethical and effective treatment plans. If the patients feel they are being taken seriously, they will be less defensive and more willing to explore the possibility that their symptoms could have psychological origins. Morgellons sufferers have been ignored, teased, and shunned for years, and it is now the responsibility of the medical community to genuinely listen.

Sitting in bedrooms across the world, faces lit by the glow of computer monitors, eyes squinted and brows furrowed, thousands of Morgies type their pleas, unable to think beyond the itch that forever altered their lives.